Wyoming is a place defined not by cities or crowds, but by silence. A silence so vast, so textured, so elemental that it becomes a presence in itself — a companion on the road, a teacher in the desert wind, a shadow beneath the high peaks of the Tetons. Here, the land unfolds in great, unbroken expanses that stretch toward horizons that seem farther than in any other state, as though distance itself were made larger in the Mountain West.

To step into Wyoming is to enter a landscape shaped more by geology and weather than by human hands. Sagebrush seas ripple beneath a dome of sky that feels impossibly tall. Red buttes rise like ancient fortresses. Rivers carve deep, secret canyons. And the wind — always the wind — moves through it all, clean, fierce, and timeless. This is the wind that shaped cowboys and ranchers, that carved the paths of bison and pronghorn, that still whispers through fences and open rangeland in a voice older than settlement.

Wyoming’s beauty is monumental, yet intimate. The volcanic breath of Yellowstone, the perfect alpine geometry of the Tetons, the quiet dignity of the Bighorns, the desert austerity of the Red Desert, the gentle charm of small towns like Lander, Buffalo, and Cody — each reveals another angle of the state’s character. Its communities feel steadfast and sincere, shaped by isolation, resilience, and a profound sense of place.

This is the least populated state in America, and that feels like its greatest luxury. Roads stretch for miles without interruption. Night skies glow with stars so bright they seem to vibrate. Wildlife roams freely — not in pockets, but across entire ranges and valleys. Wyoming is not a state you observe; it is one you inhabit, breathe, and absorb.

It offers something rare: the feeling of being small in the best possible way, part of a wider, older, more elemental world where landscape rules and the human spirit expands to match it.

Welcome to Wyoming — a land of wind and wonder, stone and sky, solitude and freedom.

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone is the beating heart of the American landscape — a place where the earth speaks in steam, thunder, color, and unfathomable depth. Beneath its forests and meadows lies a living supervolcano, its heat rising through vents, fumaroles, mud pots, and geysers that punctuate the land with drama and mystery.

Walking through Yellowstone feels like wandering into the beginning of the world. Old Faithful erupts in a pillar of white steam against a wide blue sky. Grand Prismatic Spring shimmers with impossible colors: turquoise center, radiating rings of orange and gold like a living watercolor. Rivers run warm and silvery with minerals, lined with bison tracks and the white bones of fallen trees calcified by time.

The wildlife feels like an open-air encyclopedia of American ecology. Bison herds rumble across the Hayden Valley, their silhouettes monumental against morning fog. Wolves call through the Lamar Valley at dusk, reclaiming territory they once lost. Elk move through meadows like quiet apparitions, and the shadow of a grizzly occasionally sweeps the ridges.

Then comes the canyon — the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, a cathedral of volcanic stone carved by the river that roars through it. The falls plunge in golden mist, turning the air electric.

More than a park, Yellowstone is a reminder of the earth’s untamed power. It humbles, astonishes, and alters your understanding of the natural world. It is a place where creation never finished — a landscape still becoming.

Jackson

Jackson is Wyoming’s cultural frontier — a crossroads where rugged Western life meets art, cuisine, elegance, and adventure. It has the feel of a town suspended between worlds: as comfortable with ski boots as with gallery openings, as rooted in ranching as in refined hospitality.

The Town Square, with its famous elk-antler arches, radiates charm. Wooden boardwalks echo with footsteps, shops glow softly behind old-style facades, and the blend of outdoor gear stores and fine art galleries hints at the town’s dual identity. Cowboy bars with swinging doors stand steps from haute cuisine eateries, and the mix somehow feels effortless.

Jackson’s surroundings are its soul. The National Elk Refuge sits just beyond the town, a winter sanctuary where thousands of elk gather in a migration as ancient as the land itself. In summer, the town hums with hikers, river rafters, and families returning from the Tetons. In winter, skiers descend upon Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, one of the most renowned and challenging ski destinations in North America.

Art flourishes too. The National Museum of Wildlife Art, built into a hillside of stone, overlooks a rugged valley and houses masterpieces that bring Western ecology to canvas and sculpture. Its presence elevates the town from charming to culturally luminous.

Jackson is not defined by tourism but by atmosphere — lively, polished, yet authentically Western. It is the meeting point of wilderness and refinement, adventure and comfort, tradition and evolution. A place with energy, soul, and sky.

Cody

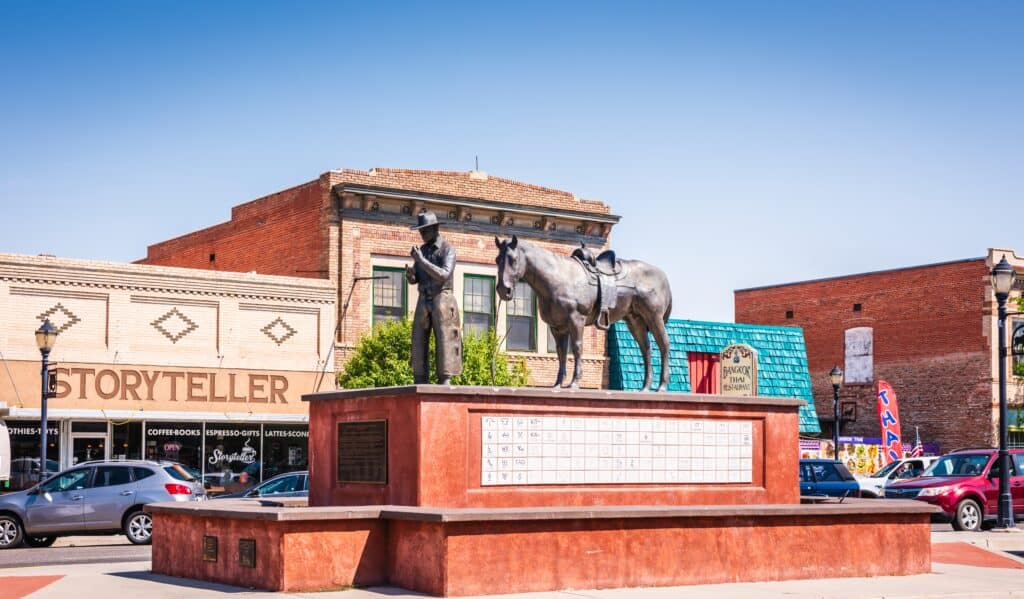

Cody is the beating heart of Wyoming’s frontier mythology — a town built on spirit, grit, and the legacy of one man: Buffalo Bill Cody. Here, the Old West is not a theme but a lineage; history breathes in the timber buildings, the long main street, and the sense that adventure has always passed through this place on its way into the high country.

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West is the town’s intellectual crown jewel. More than a museum complex, it is a reverent archive of Western art, Plains Indian culture, natural history, and firearms — a sweeping portrait of the frontier experience. Its galleries glow with landscapes and artifacts that remind visitors how wild, immense, and complicated the West once was, and still is.

Step outside, and the rhythm changes. Rodeo culture reigns here — the Cody Nite Rodeo runs all summer long, offering dust, adrenaline, and the fierce athleticism of riders who treat broncs and bulls as worthy, respected opponents. This isn’t spectacle; it’s a working heritage.

Cody’s surroundings are pure Wyoming: wide plateaus, red rock outcrops, sagebrush stretching toward distant buttes. The Buffalo Bill Scenic Byway leads west toward Yellowstone, cutting through spectacular canyon country along the North Fork of the Shoshone River. It is one of the most beautiful drives in America — a corridor of towering cliffs, vaulted skies, and a sense of leaving civilization behind.

Cody is both a tribute to the past and a gateway to the wild. It embodies Wyoming’s restless spirit, where history is not preserved behind glass — it’s lived.

Laramie

Laramie is a city shaped by altitude, wind, and intellect — a collegiate outpost perched on the high plains at 7,200 feet. It is a place where the West meets the world, where cowboys share cafes with professors, and where the sky feels so close you almost expect to hear it breathe.

Historic downtown Laramie is a small but richly textured grid of brick buildings, iron facades, train tracks, and murals that celebrate Indigenous heritage, local storytellers, and the enduring presence of the plains. Coffee shops hum softly with University of Wyoming students, galleries showcase regional artists, and old saloons carry the scent of wood, leather, and a century of conversation.

The university itself gives Laramie an academic heartbeat. From arts and theater to geology and natural sciences, the campus feels expansive and welcoming, bordered by open spaces where pronghorn graze. The American Heritage Center, an architectural landmark, houses archives of Western history and Western imagination — a fitting presence in this intellectual prairie town.

But step beyond the city limits, and Laramie becomes a door to wilderness. The Snowy Range rises just west of town, its alpine lakes shimmering among pines and granite spires. In summer, wildflowers paint meadows in bright strokes; in winter, the range transforms into a playground for snowshoers and cross-country skiers.

Laramie feels like the quiet counterpoint to Wyoming’s wilder landscapes — introspective yet grounded, cultured yet rugged, open-hearted yet remote. It is a town of both thought and frontier spirit.

Cheyenne

Cheyenne, Wyoming’s capital, is a city where history and modern life intertwine with effortless continuity — part railroad hub, part cowboy stronghold, part political center, and entirely Western at its core. The city’s name carries the weight of Indigenous history, railway ambition, and the long reach of the open plains.

Downtown Cheyenne feels dignified and warm. The Wyoming State Capitol, recently restored, gleams with sandstone brilliance beneath huge skies. Government buildings stand alongside old-time storefronts and ornate brick architecture. Historic hotels and saloons echo with stories of cattle barons, railroad workers, and legislators who shaped the state’s identity.

But Cheyenne’s true soul gallops into the spotlight every July during Cheyenne Frontier Days — “the Daddy of ’Em All,” the world’s largest outdoor rodeo. For ten days, the city becomes a celebration of bronc riding, barrel racing, parades, chuckwagon cookouts, and the storied culture of the American cowboy. It is exhilarating, boisterous, and deeply rooted in tradition.

Museums enrich the city’s narrative further. The Cheyenne Depot Museum honors the railroad legacy that built the town. The Nelson Museum of the West preserves artifacts from Indigenous nations and early settlers, offering a textured view of the region’s past.

Surrounding Cheyenne are wide, wind-brushed prairies dotted with ranches and migrating herds of pronghorn. The openness feels infinite, a reminder that even though Cheyenne is the largest city in the state, Wyoming’s spirit remains anchored in space, sky, and silence.

Cheyenne is both the ceremonial face of Wyoming and a living node of the West — proud, historic, and unmistakably authentic.

Sheridan

Sheridan sits beneath the eastern slopes of the Bighorn Mountains, a town that blends small-town calm with the sophistication of a place that has long welcomed travelers, writers, and artists seeking frontier inspiration. It is one of Wyoming’s most endearing communities — cultured, friendly, and framed by rolling green foothills that shimmer in late afternoon light.

Sheridan’s downtown is a portrait of Western refinement: brick storefronts, carefully preserved historic buildings, independent shops, and art galleries that take their craft seriously. The Sheridan Inn, once co-owned by Buffalo Bill, remains a landmark of frontier hospitality. Its wide porch invites visitors to sit, rock gently, and imagine the countless stories that unfolded here over a century.

The town is also known for traditional craftsmanship — particularly saddlemaking and leatherwork. Workshops create pieces that are artworks in their own right, linking contemporary artisans to generations of Western equestrians and ranchers.

Beyond town, the Bighorn Mountains rise with quiet majesty. Their slopes are gentle compared to the Tetons, but in their gentle folds lie meadows, trout-filled streams, aspen groves, and high alpine lakes that feel secret and sacred. Scenic drives like U.S. Highway 14 climb through canyon walls and dense forests before opening onto vast high plateaus.

Sheridan feels like Wyoming’s poetic heart — a place where nature, history, and artistry cohabitate with grace.

Casper

Casper sits along the North Platte River like a frontier crossroads reinvented for the modern age — a place where Wyoming’s mining, ranching, and pioneering histories converge with museums, outdoor recreation, and a vibrant, steadily evolving downtown. It is a city shaped by geological time and human determination, by fossil beds and wind, by the slow, powerful rivers that have carried migrants west for centuries.

The National Historic Trails Interpretive Center is Casper’s cultural nucleus — a thoughtful, beautifully designed museum overlooking the city from a sandstone bluff. It tells the stories of the Oregon, Mormon, California, and Pony Express Trails, weaving together accounts of hardship, grit, and hope. Standing inside its panoramic windows, you can almost see wagon wheels creaking along the horizon.

Casper Mountain rises directly south of town, its forested slopes offering cool alpine respite in summer and snowbound adventure in winter. Trails lead past aspen groves, crashing streams, and quiet overlooks where ravens wheel on thermals. In warmer months, the mountain’s meadows ignite with wildflowers; in colder seasons, groomed runs draw skiers and snowmobilers.

Down in the valley, the North Platte River glides steadily through town, its clear waters beloved by anglers seeking trout under golden evening light. A growing network of trails and parks along the riverfront makes Casper unexpectedly scenic.

Downtown Casper has an industrious charm — brick facades, theaters, breweries, and a renewed sense of civic pride. It’s a city with frontier bones and a contemporary soul, a place that doesn’t pretend to be flashy but feels profoundly grounded.

Thermopolis

Thermopolis is Wyoming’s warm heart — literally. Home to the world’s largest mineral hot spring, this small town in the Wind River Canyon region has attracted visitors for centuries with healing waters, dramatic landscapes, and a soothing, unhurried ambiance.

Hot Springs State Park is the centerpiece. Here, mineral-rich water surges from the earth at a stunning 135°F before spilling into terraced pools, steaming streams, and soothing bathhouses. The park’s free bathhouse feels almost mythic — a modern echo of ancient traditions of healing. Walking across the park’s suspension bridge, you smell the mineral-rich air and hear the soft hiss of geothermal water, a sound that seems almost alive.

Beyond the springs, the landscape unfolds with cinematic drama. North of town, stratified cliffs glow orange and gold. South of town, the Wind River Canyon carves a deep, towering gorge through ancient rock older than the mountains themselves. Driving through it is one of Wyoming’s great geological pilgrimages — layer upon layer of time rising on both sides of the highway.

Thermopolis also surprises with its prehistoric richness. The Wyoming Dinosaur Center is one of the finest fossil museums in the West, featuring full skeletons, active dig sites, and an intimate perspective on a region once roamed by giants. Few places allow visitors to stand on ground where dinosaurs were uncovered just days or weeks earlier.

The town itself is peaceful, friendly, and slow-paced — the kind of place where conversations unfold easily and the river moves at a calm, steady rhythm.

Thermopolis is Wyoming distilled into warmth, water, and wonder — a restorative oasis in a rugged landscape.

Dubois

Dubois (pronounced DOO-boyz) is one of Wyoming’s most atmospheric mountain towns — a quiet valley settlement where the Absaroka Range rises in jagged silhouettes and the Wind River drifts through sagebrush plains. It feels remote in the most enchanting way, as if the rest of the world recedes the moment you arrive.

The town has the charm of an old log-built Western outpost. Wooden boardwalks, rustic storefronts, and hand-carved signs create a timeless frontier aesthetic. Yet Dubois is not a museum piece — it’s a living ranching community infused with creativity from artisans, outfitters, and wildlife experts who call this valley home.

The surrounding landscape is dramatic and varied. To the north, the Absarokas erupt in volcanic spires, red cliffs, and deep forested canyons. To the south, the Wind River Range rises in a serene granite rampart. This diversity makes Dubois a paradise for hikers, horseback riders, and backcountry wanderers.

Dubois is also one of the best gateways to Wyoming’s wildlife. Herds of bighorn sheep roam the mountains in numbers rarely seen elsewhere; the National Bighorn Sheep Center celebrates this heritage with exhibits and guided trips into wild country where the animals thrive.

The road toward Togwotee Pass leads travelers through a wonderland of alpine meadows, ghost forests, and sweeping views of the Tetons appearing suddenly like a revelation. In winter, snowmobilers roam some of the West’s finest powder fields.

Dubois is quiet but powerful — a place where the land speaks loudly in color, climate, and silence. It is Wyoming at its most contemplative and scenic.

Powell

Powell lies in the wide, sunlit expanse of Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin, a landscape defined by long horizons, irrigated fields, and the distant silhouettes of mountains rising like ancient guardians. It is an agricultural heartland shaped by ingenuity — a place where early settlers channeled mountain water into fertile ground, transforming desert sage into thriving farmland. That legacy still defines Powell today, giving the town a sense of resilience and grounded practicality.

At its core stands Northwest College, a small but spirited institution that brings international students, cultural events, and youthful energy to a town otherwise steeped in ranching and farming traditions. Its presence adds layers of thoughtfulness and creativity to the community — a quiet intellectual heartbeat on the high plains.

Just outside Powell, the landscape reveals its wild, rugged nature. The drive toward the Shoshone Canyon or the Beartooth foothills offers dramatic vistas of eroded cliffs, red rock alcoves, and sweeping grassland where pronghorn dash under open skies. To the west lies the route to Yellowstone, making Powell a gateway to one of the world’s great wildernesses.

The Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, located a short drive from town, is one of Wyoming’s most poignant historical landmarks. Here, thousands of Japanese Americans were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. The center’s exhibits, stories, and preserved structures form an emotional, essential narrative — a reminder that even beautiful landscapes can harbor difficult histories.

Downtown Powell is friendly, modest, and welcoming, with diners, outfitters, and stores that still carry the cadence of small-town living. It’s not a place of spectacle but of substance — a community built by water, wind, and generations determined to thrive in the high desert’s embrace.

Rock Springs

Rock Springs stands anchored in the austere beauty of southwestern Wyoming, where mesas, coal seams, and wind-carved buttes dominate the horizon. This is a place born from the earth — a town shaped by mining, railroad expansion, and waves of immigrant labor that gave Rock Springs a cultural diversity unexpected for such a remote landscape. Its historic districts still carry traces of Welsh, Polish, Italian, and Chinese communities who fueled the region’s early coal boom.

Walking through the Historic Downtown, you feel a sense of tough, gritty pride. Brick buildings lean into Wyoming’s relentless wind; murals and storefronts speak to a town that has endured, adapted, and reinvented itself as energy cycles rise and fall.

But Rock Springs is also a gateway to one of Wyoming’s most underrated natural regions: the Red Desert. This vast, haunting wilderness of shifting sand dunes, sagebrush seas, and cracked clay basins stretches into the horizon like a forgotten planet. Here you’ll find the Killpecker Sand Dunes, among the largest active dune fields in North America, and the Boar’s Tusk, a volcanic plug rising like a dark monolith from pale earth.

Nearby, Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area offers a dramatic contrast — a deep, winding reservoir glowing turquoise against blazing red cliffs. Boating, hiking, and fishing unfold against a backdrop that looks carved by giants.

Wild horses roam the region, especially in the stewardship areas east and north of town. Sightings are common: a stallion cresting a ridge, a band of mares trotting across open sage, their manes lifted by the desert wind.

Rock Springs may not be polished, but it is real, elemental, and deeply tied to Wyoming’s geological soul. It is a land of raw edges and vast silence — a frontier in spirit as much as geography.

Pinedale

Pinedale is Wyoming distilled into pure mountain essence — a small, rugged town pressed between the towering Wind River Range to the east and rolling sagebrush plains to the west. It is a place where wilderness begins at the edge of the sidewalk and where the rhythm of life still bends around weather, wildlife, and the lure of the high country.

The town serves as the principal gateway to the Wind River Range, arguably one of the most striking and pristine mountain ranges in North America. Here, jagged granite peaks rise like cathedral spires, glaciers cling to shadowed cirques, and alpine lakes shimmer in impossible blues. Trails from Elkhart Park and Green River Lakes lead deep into the wilderness, where the Continental Divide arcs into some of the wildest terrain left in the Lower 48.

Pinedale’s identity has long been shaped by the legacy of trappers and mountain men. The Museum of the Mountain Man preserves this heritage with immersive exhibits that evoke the fur trade era — beaver pelts, flintlocks, journals, and stories of survival. Every year, the Green River Rendezvous brings history to life as reenactors, traders, and craftsmen gather in a spirited celebration that feels like a time warp into the 19th century.

Just north of town, Fremont Lake stretches out beneath high glacial moraines, its cold, clear waters providing boating, fishing, and quiet evenings under immense skies. Moose wander willow flats; bald eagles glide over turquoise water.

Pinedale is the kind of town where early mornings smell of pine and woodsmoke, where locals know their mountains intimately, and where the wilderness is not a distant idea but a daily companion. It is Wyoming at its most unspoiled and breathtaking.

Evanston

Evanston feels like a frontier town perched at the threshold of two worlds: the high sage deserts of Wyoming and the forested mountains of Utah’s Wasatch Range. Its history is written in iron and steam — a place shaped profoundly by the Union Pacific Railroad, whose engines once thundered through town carrying the new America westward. Many of Evanston’s most distinctive buildings, including the restored Roundhouse and Railyards Complex, still echo with this industrial legacy, their brick facades now transformed into cultural spaces that honor the ingenuity and grit of early railroad workers.

Yet Evanston is far more than a relic of the rails. It is also a gateway to serene mountain wilderness. To the south sprawl the wooded slopes of the Uinta Mountains, where alpine lakes, hidden meadows, and crisp, cold streams invite hikers, anglers, and backcountry wanderers. The nearby Bear River State Park offers a gentler landscape — cottonwood-lined paths, quiet picnic areas, and a resident herd of bison and elk grazing in wide, wind-swept fields.

Downtown Evanston retains an unexpectedly cosmopolitan flair, shaped in part by the historic presence of Chinese railroad laborers whose legacy is honored today through the annual Chinese New Year Festival and the evocative Joss House site. Victorian storefronts, antique shops, and local cafés lend a warmth to the old streets, especially when winter snow settles over the rooftops.

There is a sense in Evanston that the frontier never fully disappeared — it simply matured. The horizon still stretches unbroken, the air carries a crisp mountain sharpness, and the rhythm of life feels grounded, steady, and resilient. Evanston stands as a threshold town: rooted in history, embraced by wilderness, and unmistakably Wyoming.

Kemmerer

In southwest Wyoming, where rolling sagebrush plains meet quiet limestone ridges, lies Kemmerer — a town defined by both its deep geologic time and its strikingly human history. On the surface, Kemmerer appears modest, but beneath its soil lies one of the world’s richest windows into the ancient past: Fossil Butte National Monument. Here, millions of years ago, an enormous subtropical lake covered the region. Today, its perfectly preserved fossils — delicate fish, palm fronds, insects, even turtles and birds — rest in limestone layers like pages of a stone-bound book. Visiting Fossil Butte is to witness prehistory frozen in immaculate detail.

Kemmerer is also known as the Birthplace of J.C. Penney, where the chain’s first-ever store still stands. The simple storefront remains preserved, offering a tangible reminder of early American entrepreneurship and the modest beginnings of a name that would one day span the nation.

The surrounding landscape is classic Wyoming: broad skies, rugged sage country, and sandstone bluffs that glow in late-afternoon light. Wildlife often wanders close — mule deer grazing at dusk, pronghorn sprinting across open flats, and hawks circling above the long, quiet ridgelines. Outdoor explorers will find serene fishing and camping around the nearby Hams Fork River and glacial remnants of alpine lakes up in the mountains to the north.

Kemmerer has the feel of a place suspended between epochs — a town where fossils whisper stories from 50 million years ago, where small-town Americana lives on, and where the modern world remains distant enough that the nights still end in true darkness. Under the sweeping constellations of the Wyoming sky, Kemmerer becomes a meeting point of past and present, of rock and story, of vast landscape and quiet community.

Greybull

Greybull rests at the confluence of the Bighorn and Greybull Rivers, embraced by dry, sweeping plains and rimmed by distant mountain silhouettes. It is a crossroads town — a place where the routes between Cody, Sheridan, and the Bighorn Basin converge, making Greybull both a pause and a passage in the traveler’s journey through northern Wyoming.

The beauty here is understated but unmistakable. Just outside town, eroded badlands and uplifted cliffs reveal layers of ancient sediment in muted tans, reds, and grays. The land feels wide and exposed, shaped by wind, water, and deep time. Wildlife thrives in this open country: pronghorn grazing near fencelines, coyotes trotting along the horizon, and golden eagles drifting on thermals high above the basin.

Greybull’s most intriguing attraction is the Museum of Flight and Aerial Firefighting, an unexpected aviation landmark that honors the heroic — and often perilous — work of aerial firefighters. Vintage aircraft, engines, and historical exhibits bring the world of wildfire aviation to life in a vivid and moving way, paying tribute to a profession deeply tied to the American West.

A short drive away lies Shell Canyon, a geological marvel where the road rises into the Bighorn Mountains past roaring waterfalls, layered canyon walls, and narrow mountain gorges. The colors of the canyon — deep rust, gray limestone, and splashes of green from cottonwoods — make it one of Wyoming’s finest hidden gems.

Greybull itself is quiet, friendly, and grounded. Its streets reflect the easy pace of rural Wyoming life: cafés where ranchers gather at dawn, local shops that still greet customers by name, and long evenings touched by the warm glow of sunset across the western plains. In Greybull, simplicity becomes a kind of elegance.

Buffalo

Buffalo sits comfortably at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains, where rolling foothills meet the first rise of pine-covered peaks. It feels like the kind of Western town imagined in novels — historic, warm, and graced with a deep sense of continuity between past and present. Its main street, lined with Victorian storefronts and weathered brick buildings, is anchored by the legendary Occidental Hotel, a living relic of the Old West where Butch Cassidy, Buffalo Bill, and Calamity Jane once crossed the polished wooden floors.

Buffalo’s charm comes partly from its intimacy and partly from its setting. The Clear Creek runs right through town, its waters cold and quick, fed by snowmelt from the high Bighorns. Locals gather along its banks for summer picnics, fly-fishing, or simply listening to the water spill over stone and gravel. The town’s parks and tree-lined neighborhoods give it a homey, lived-in feel that contrasts with the dramatic wilderness beyond.

To the west, the Bighorns rise in steep, forested waves. Trails lead into the Cloud Peak Wilderness, where granite peaks thrust upward and hidden alpine lakes lie cupped between ridgelines. It’s a landscape defined by its purity — crisp air, dense spruce forests, and meadows blooming with wildflowers. Wildlife is abundant: moose browsing willows, black bears moving through berry patches, and elk herds grazing high on the ridges.

Buffalo is a place where history breathes through the streets, where mountains shape daily life, and where the West feels close enough to touch. The sunsets here — soft, peach-colored, and stretched across endless sky — give the quiet evening air a sense of promise.

Sundance

Sundance lies beneath the watchful shadow of Sundance Mountain, in a corner of Wyoming touched by legend and framed by the rolling Black Hills. It is a small town with an outsize place in Western lore — the spot where the Sundance Kid allegedly earned his name after a stint in the local jail. Today, the story is woven into the town’s identity, but Sundance offers far more than outlaw myth.

The streets are peaceful, lined with shops, cafés, and local businesses that retain a warm, homegrown authenticity. The Crook County Museum provides an engaging window into regional history, from Native American heritage to frontier settlers, ranching families, and the colorful characters who drifted through the Black Hills during their most tumultuous years.

Just outside town, the Black Hills rise in quiet grandeur. They are gentler than Wyoming’s western ranges — more intimate, with ponderosa pines, rounded granite outcrops, and lush meadows unfolding in soft undulations. Wildlife moves easily through this landscape: deer among the trees, wild turkeys along the roadways, and hawks riding thermals above the hills.

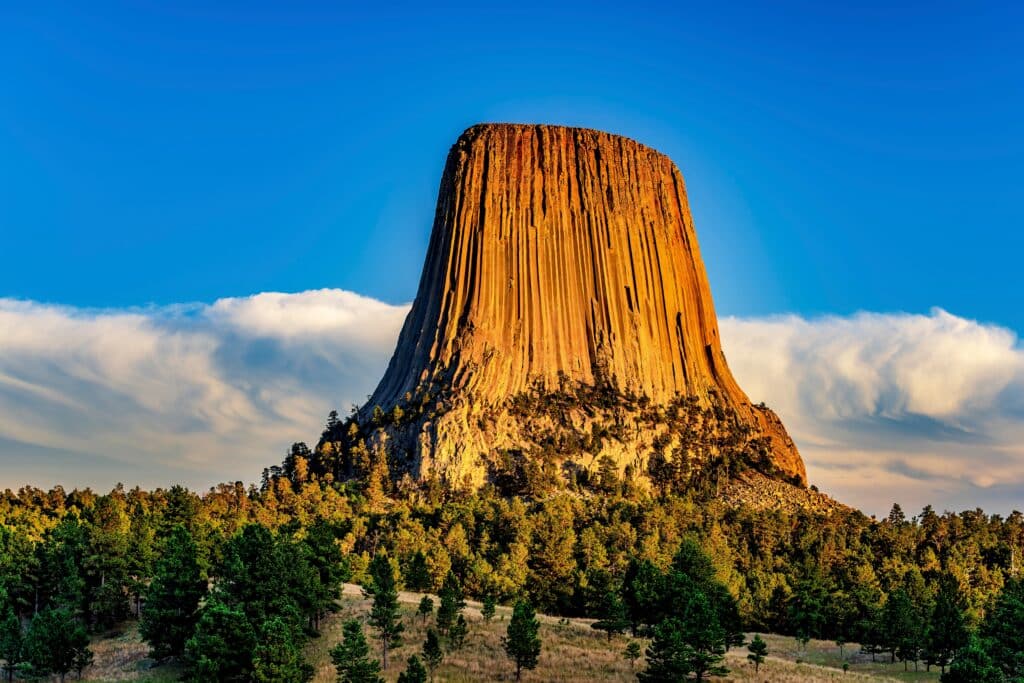

The nearby Keyhole State Park adds shimmering blue to the scene, its reservoir reflecting prairie clouds and offering boating, fishing, and warm summer relaxation. Farther east lies the iconic Devils Tower, a monolithic column of volcanic rock sacred to Native tribes and mesmerizing to all who stand beneath it. From Sundance, the journey to Devils Tower is short but unforgettable, winding through pine forests and open prairie before the tower appears like a geological miracle on the horizon.

Sundance feels like a quiet frontier town with a deep sense of place — a sanctuary of pine-scented air, layered history, and Black Hills magic.

Lovell

Lovell rests along the northern edge of the Bighorn Basin, a gateway to shimmering lakes, rugged canyons, and the wild, echoing country that defines northern Wyoming. Its streets are wide and modest, framed by views of distant ridgelines and the fertile fields fed by the Shoshone River. Agriculture shapes the town — sugar beets, alfalfa, and small farms that speak to generations who coaxed harvests from arid land through perseverance and irrigation.

But Lovell’s significance lies in its proximity to two extraordinary natural treasures. First is the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, where the earth splits open into a towering chasm of red rock and deep green water. The canyon’s cliffs rise dramatically, sometimes sheer for hundreds of feet, while the lake below winds through its heart like a hidden ribbon. Boat tours, trails, and overlook points offer breathtaking perspectives on a landscape as bold as anything in the American West — grand, windswept, and strangely serene.

Second is the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range, home to one of America’s most genetically significant wild horse herds. The mustangs here are descendants of Spanish colonial horses, and spotting them among the sage, juniper, and rocky plateaus is a rare and moving experience. Their silhouettes against the horizon evoke a sense of ancient freedom.

Back in town, Lovell’s community is gentle and welcoming. Local diners serve hearty comfort food; summer festivals bring neighbors together; evenings settle into a quiet stillness under bright, unbroken stars.

Lovell may appear unassuming at first glance, but it is surrounded by some of Wyoming’s most stirring landscapes — a place where solitude, beauty, and wild grace meet at the edge of the canyon winds.

Wheatland

Wheatland lies in southeastern Wyoming’s wide-open prairie country — a landscape that feels carved from wind, sunlight, and spaciousness. The town sits at the base of the Laramie Range, where the dry blond fields begin to lean upward toward granite outcrops and sturdy forests. The simplicity of Wheatland is part of its charm: quiet main streets, farm stores, and the steady rhythm of a community rooted in agriculture.

It’s a place defined by sky. Clouds move across the horizon with slow, theatrical grandeur; sunsets stretch in bands of rose and gold; summer storms sweep in like fast-moving shadows. The land here is open, honest, and hardworking — much like the people who have tended it for generations.

The Wheatland Reservoirs, especially No. 3, are local gems, drawing anglers, campers, and waterfowl. Wind brushes across the surface in restless patterns while pelicans gather in bright white clusters. To the west rises Laramie Peak, a rugged summit that towers above the plains, its granite flanks catching morning light like a signal fire. Trails wind through ponderosa forests, meadows bright with wildflowers, and quiet ridges where mule deer graze in early dawn.

Just outside town lies Greyrocks Reservoir, tucked into rocky hills, offering solitude, shorelines, and warm-summer wilderness. Pronghorn antelope roam the surrounding fields, moving with that peculiar combination of elegance and nervous speed.

Wheatland may not appear dramatic at first glance, but spend time here and you feel the subtle pull of prairie life — the beauty of uncomplicated days, the scent of cut hay drifting across the fields, and the wide Wyoming sky arching endlessly overhead.

Lander

Lander sits where the mountains meet the desert — a frontier town of blue skies, climbing crags, and a distinctive spirit of adventure. Nestled along the Popo Agie River and backed by the dramatic Wind River Range, Lander feels like a gateway to two worlds: the rugged high peaks to the west and the red desert plateaus of central Wyoming to the south.

The town is alive with outdoor culture. Climbers gather at cafés discussing routes and conditions; backpackers stock up before heading into the backcountry; and residents move with a quiet ease, as if accustomed to waking every day with mountains at their doorstep. The Sinks Canyon State Park, just minutes from town, is one of Wyoming’s most unique landscapes — where the Popo Agie River vanishes into a limestone cavern (“the Sinks”) and reappears hundreds of yards downstream in a deep pool (“the Rise”). The canyon walls rise steeply, home to cliffs that glow amber and gold in late afternoon light.

From Lander, trails climb toward the Wind River Range, one of the most breathtaking and remote mountain systems in America. Granite domes, glacier-carved valleys, and more than a hundred alpine lakes fill a world of silence and snow-fed beauty. It’s a place that rewards solitude, resilience, and reverence.

Lander’s town center blends Western charm with modern creativity — breweries, artisan shops, outfitters, and historic brick buildings. Evenings settle into a relaxed hum as the mountains turn violet and the sound of the river threads through the cottonwoods.

Lander feels both wild and welcoming — a place where the horizon stretches, the mountains rise boldly, and the spirit of Wyoming stands clear and unmistakable.

Mountain View

Mountain View rests in a wide, high valley of sagebrush plains and distant peaks — a quiet community shaped by open horizons and the steady rhythms of ranch life. The town is small, but its landscapes feel expansive: big skies overhead, long dirt roads stretching toward the Uintas, and a sense of peaceful distance that settles into the bones.

Life here unfolds at its own pace. Morning light warms the sage; windmills spin lazily against pale-blue skies; horses graze in fenced pastures with the mountains rising faintly behind them. Mountain View is part of a trio of sister communities — along with Fort Bridger and Lyman — that help hold together this far western corner of Wyoming. The land is crisp and almost austere, but it rewards those who appreciate quiet beauty.

The region’s great treasure is the proximity to the Uinta Mountains, with trailheads that lead into lush forests, alpine lakes, and rock-strewn plateaus. Summer brings cool nights, bright stars, and the sound of rivers tumbling over smooth granite. Winter arrives clean and sharp, turning the valley into a landscape of frost and stillness.

Nearby lies Fort Bridger State Historic Site, one of Wyoming’s most evocative windows into the past. Here, wagon ruts, log structures, and old military buildings whisper the story of westward migration, trading posts, and frontier survival.

Mountain View’s charm is its simplicity — a place that avoids spectacle yet offers a soul-refreshing sense of space. It is Wyoming in its most uncluttered form: wind-swept, quietly resilient, and honest in its beauty.

Ten Sleep

Ten Sleep sits cradled at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains, a small town with a poetic name and landscapes worthy of it. The name itself comes from an old Native counting system, marking the distance — ten nights’ travel — between key tribal camps. Today, the town remains a waypoint of sorts: a peaceful valley community fringed by dramatic canyon walls and endless outdoor possibilities.

The centerpiece of the region is Ten Sleep Canyon, a massive limestone gorge carved by the clear, fast-moving Ten Sleep Creek. The canyon’s cliffs rise like cathedrals of pale stone, attracting climbers from around the world who test themselves on thousands of routes bolted into the white walls. But even non-climbers feel the canyon’s power: the sound of the creek rushing, the swaying pines, the way the canyon narrows into shadow before bursting open into sunlit meadows.

The town of Ten Sleep is warm and welcoming, with cafés, a charming general store, and the famed Ten Sleep Brewing Company, where locals and travelers share stories beneath big skies and starlit evenings. Summer brings festivals, rodeos, and music that echoes against the surrounding hills.

To the east, the Bighorn Mountains lift into a world of alpine lakes, wildflower basins, and ridgelines where wind shapes the grass into silver waves. Trails wander through quiet forests scented with pine and sage, often leading to viewpoints where the whole valley spreads out in soft greens and tans far below.

Ten Sleep is a place where time loosens its grip — where landscapes still feel wild, where community remains tight-knit, and where the canyon, the creek, and the mountains create a harmony found in few other corners of Wyoming.

Alpine

Alpine lies where three great Wyoming waters meet — the Snake, the Salt, and the Greys Rivers — a town built on the musical convergence of currents and the shadow of rising mountains. Surrounded by rugged peaks and the shimmering fingers of Palisades Reservoir, Alpine feels like a place suspended between movement and calm, a crossroads of river life and alpine wilderness.

The reservoir stretches long and serene, a corridor of deep blue framed by steep, forested slopes. In summer, its quiet coves fill with the hum of boats and the soft swish of paddles. Fishermen drift through morning fog in search of trout, while the mountain walls catch the day’s earliest light and scatter it in glowing tones of gold and pink. When the water’s low in winter, the shoreline reveals stone terraces and river scars, quiet reminders of geological time.

Alpine marks the gateway to the Snake River Canyon, one of the most scenic drives in Wyoming. The river charges through it, white and restless, drawing rafters and adventurers who relish its rapids. The canyon walls rise in dramatic sweeps of granite and pine, creating a rolling dialogue between stone and water.

The town itself is cozy and friendly — a collection of mountain cabins, warm lodges, and local eateries where travelers dry off from river spray or warm up after snowy excursions. Winter blankets Alpine in deep silence as snow gathers on pine boughs, yet life continues: snowmobilers carve trails across powder meadows, and wildlife descends from the high country to the valley floor.

Alpine is both an escape and a portal — a place where mountains, rivers, and sky share equal weight, offering a quiet but unforgettable intimacy with Wyoming’s wild heart.

Newcastle

Newcastle stands in Wyoming’s far northeastern shoulder, where the rolling prairies begin to ripple into the Black Hills — that mysterious cluster of forested, ancient granite rising unexpectedly from the grasslands. The town feels quietly industrious, shaped by railroads, mining, and a deep respect for the land’s subtler beauty.

The pace is unhurried. Streets lined with brick storefronts and small cafés speak to a community that values stability and neighborliness. But the true magic of Newcastle is found in the landscapes just beyond its borders. Drive a few minutes, and the prairie subtly shifts into pine-clad hills, where the air grows cooler and scented with resin.

This region is home to the Black Hills National Forest’s western edge, a place of rugged outcrops, sandstone cliffs, and grasslands dotted with deer, wild turkeys, and grazing antelope. Trails wind through ponderosa forests that glow orange at sunset, and the wind moves through the pines like a whispered chant. It’s a gentler, more intimate wilderness than the Grand Tetons or Absarokas, but no less soulful.

Nearby stands Downtown’s Anna Miller Museum, a former sandstone armory turned local museum that preserves the region’s frontier stories — railroad expansion, ranching families, and the layered history of the Black Hills. To the west lies access to the Thunder Basin National Grassland, where sky and land seem to merge in shimmering waves of blue and gold.

Newcastle is a threshold — a place where prairie meets forest, where the American West softens into rolling forms without losing any of its frontier spirit. It invites quiet exploration, long drives, small discoveries, and a deeper appreciation for Wyoming’s subtle and varied landscapes.

Shell

Shell is small — barely more than a bend in the road — but its landscapes are vast, dramatic, and strangely haunting. It sits along the western base of the Bighorn Mountains, near the entrance to one of the state’s most extraordinary geological marvels: Shell Canyon.

The canyon begins abruptly, its walls striped with color like a layered cake of time. Reds, yellows, whites, and deep purples reveal millions of years of sediment uplifted and carved by ancient waters. The Shell Creek flows through it, clear and quick, leaping over boulders and sharpening the stone as it goes. Along the canyon walls, bighorn sheep cling to ledges and gaze calmly at travelers who wind their way upward toward the mountains.

At the base of the canyon sits Shell Falls, where water plunges into a deep granite bowl, roaring with spectacular force. A small interpretive center explains the canyon’s geological story — a tale of inland seas, prehistoric eras, and the restless tectonics that shaped the Bighorns into their present form.

The town of Shell itself feels timeless: wide-open fields, old barns curling at the edges, and dirt roads that catch the sun in swirling dust. It is a place where solitude is not an escape but a natural condition. The air is warm with sage, and the horizons seem to breathe.

Above Shell rises the Bighorn high country — plateaus dotted with lakes, quiet forests, and cliffs kissed by pink light at dawn. It’s a wilderness that feels both near and infinite.

Shell is one of Wyoming’s quiet miracles: small in population, immense in spirit, and framed by some of the most arresting geological landscapes in the American West.

Guernsey

Guernsey sits beside the slow, broad sweep of the North Platte River, a town that carries the living memory of the great migrations westward. Here, history feels unusually tactile — you can walk it, touch it, stand inside it. The region was a crucial crossing point for thousands of emigrants heading along the Oregon, Mormon, and California Trails, and their presence remains deeply imprinted on the land.

The most poignant of these traces are the Guernsey Ruts, where pioneer wagon wheels carved deep grooves into soft sandstone. The ruts dip so dramatically that they resemble ancient chariot tracks, a physical testament to endurance, hardship, and the relentless pursuit of hope. Standing in them, you feel transported — the sky wide, the wind whispering, the earth holding stories of courage and loss.

Nearby lies Register Cliff, one of the most iconic emigrant landmarks in the West. Travelers carved their names into the limestone wall as they passed, leaving behind dates, initials, and fragments of personal history. It is a touching reminder that the American West was not an abstract wilderness but a journey made by individuals, one difficult mile at a time.

Guernsey State Park adds another layer of beauty and introspection. Designed partly by the Civilian Conservation Corps, its stone structures blend harmoniously with the landscape — cliffs, river overlooks, cottonwood groves, and gentle trails where deer move through the grasses at dusk.

The town itself is friendly and unassuming, shaped by agriculture, trains, and its deep historical connection to America’s great overland era. Guernsey reminds travelers that landscapes are not only scenic — they are witnesses. And here, the land remembers everything.

Grand Teton National Park

The Teton Range rises directly from the valley floor without foothills or warning — jagged, abrupt, breathtaking. Few mountain ranges in the world create such immediate drama. Their silhouettes pierce the sky, clean and angular, like the edge of a giant stone blade.

But beneath their wild geometry lies a valley of extraordinary calm: Jackson Hole, a wide basin of cottonwoods, meadows, braided rivers, and slow-moving wildlife. Moose feed in the shadows of willow thickets. Elk drift silently across open fields. Trumpeter swans glide over calm waters, their reflections doubling the beauty.

Every viewpoint in Grand Teton National Park feels iconic. The Oxbow Bend mirror of Mount Moran at sunrise. The historic Mormon Row barns beneath the storm-lit Tetons. The glacial sheen of Jenny Lake with peaks rising sheer from its shores.

The mountains are a climber’s cathedral — steep granite faces, technical ascents, and the sacred pull of the high country. Yet the park also rewards quieter communion: a lakeshore picnic in alpine air, a hike through wildflower meadows in July, a moment of absolute stillness as the alpenglow turns the peaks rose-gold.

If Yellowstone is the earth’s fire, the Tetons are its sculpture — perfect, unyielding, eternal. Standing here, you feel the convergence of grandeur and peace that defines Wyoming’s soul.